The internet has rapidly evolved to become a profoundly powerful medium in its relatively short history, as Max Roser discusses in this post for Our World in Data. Since the first computer-to-computer connection was established via the ARPANET in 1969, the internet has been adopted around the world much faster than previous technological innovations. We are now empowered by the capacity to share unprecedented amounts of information in the blink of an eye, thus integrating the planet and revolutionising how we communicate. The internet has encouraged engagement in civic and political life (D’Alessandro and Dosa, 2001; Jenkins et al., 2009)1, 2, and galvanized international trade. Such is the magnitude of this technological seismic shift that we are said to be experiencing a Digital Revolution that is characterised by a global ‘network society’ (Castells, 2009)3.

But while almost half of the world’s population now have access to the internet, some concerning trends in the diffusion of information and communication technology (ICT) have arisen: access to the internet is unevenly distributed, and the prima facie correlate is income. If left unchecked, this pattern threatens to offset the potential benefits of the internet, and even perpetuate pre-existing problems, as those who are unable to access the internet will become socially and economically isolated. This post discusses the nature and nuances of the Digital Divide.

Firstly, it is worth noting that the so-called 'gap' in physical access to the internet has narrowed in recent years. This doesn’t illustrate the bigger picture, however. Recently, ICT scholars have widened the scope of the Digital Divide to include the quality of internet access – in terms of connection speed – as well as the technological competence of individuals.

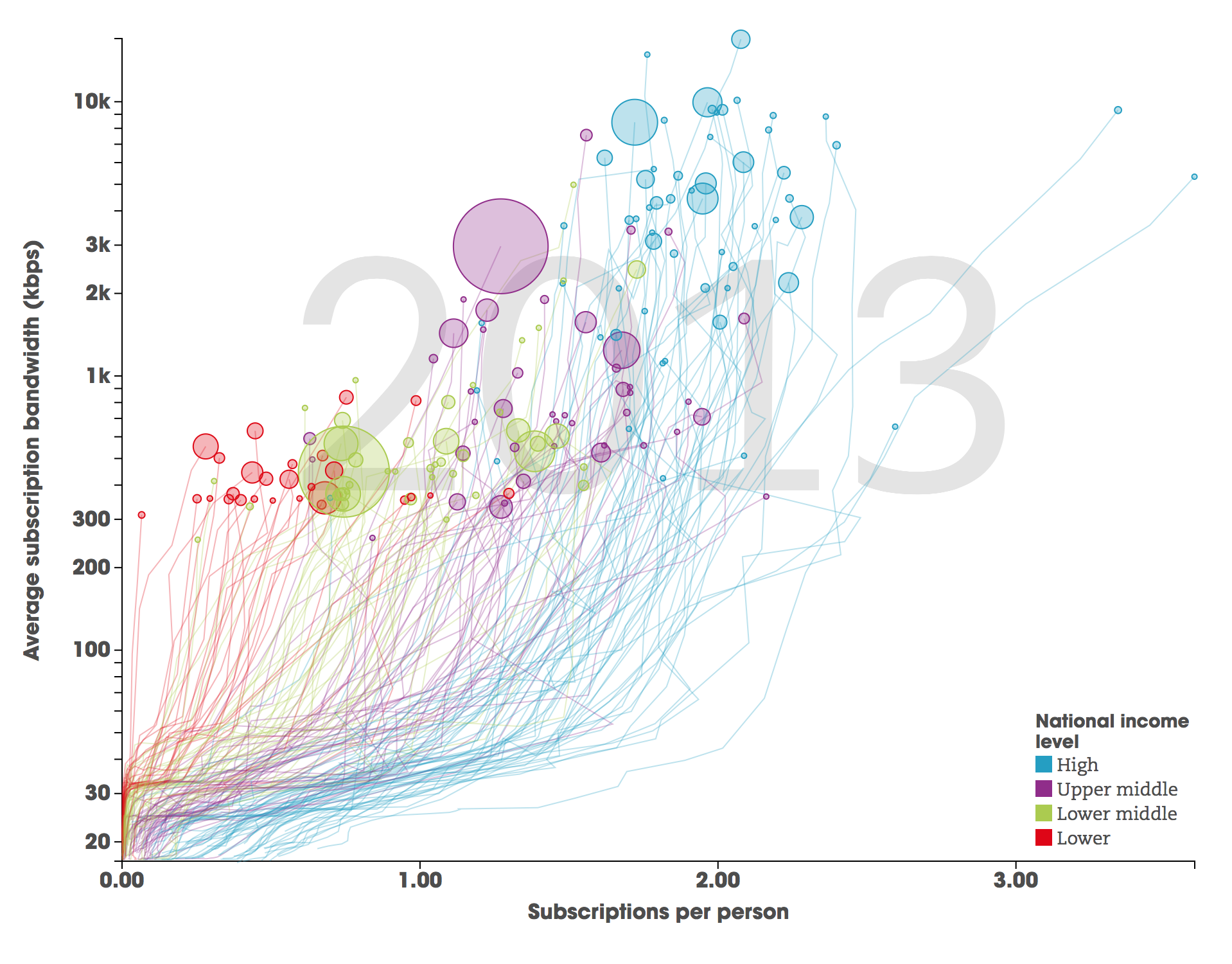

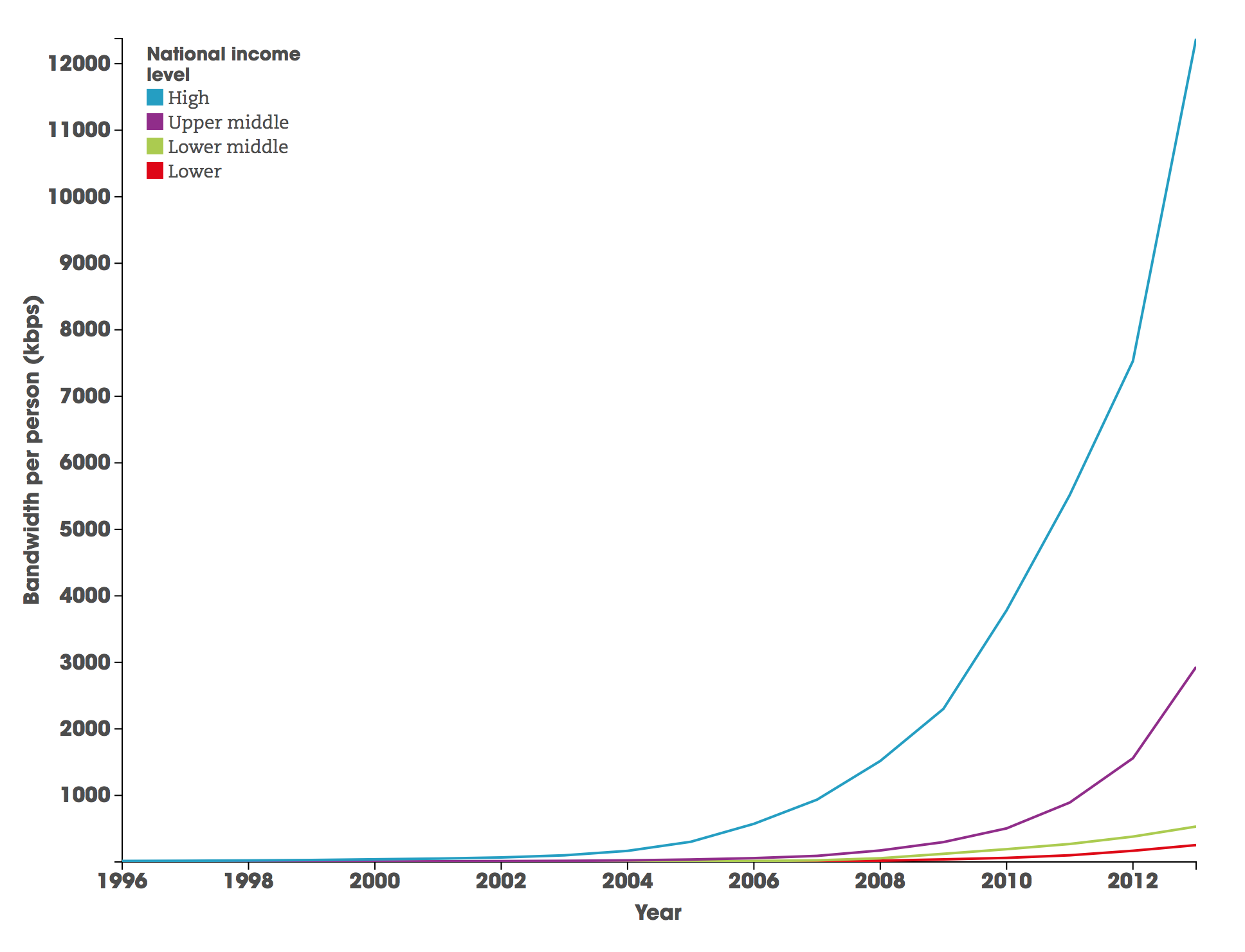

The following charts - produced by Kiln - offer a different perspective on the Digital Divide by illustrating differences in average internet capacity, or how much data each person can exchange through their device in each country at a given point in time. They clearly show that the Digital Divide in terms of bandwidth is not closing. South Korea has the highest average internet capacity with almost 17,000 kpbs, while the lowest is found in the island nation of Kiribati with 252.85 kpbs. In general, high income countries have an average bandwidth per person of almost 12,500 kbps, whereas lower income countries have about 250 kbps – to put this into perspective, it takes around 4,000 kbps to stream videos on Netflix (Hilbert and López, 2011)4. Interestingly, there is a positive correlation between international trade with the quantity and quality of internet access, and speed is more important for developing countries than the number of subscriptions (Abeliansky and Hilbert, 2016)5. And so when connection speeds by country are taken into account, the Digital Divide becomes more complex.

Other studies have suggested that the difference in ICT skills access is also significant. Generally, they have revealed the range in skills is larger than that of physical access: while the latter is narrowing in developed countries, the former is in fact growing. Further interesting results are that there is positive correlation between traditional literacy and digital information skills, and that “people learn more of these skills in practice, by trial and error, than in formal educational settings” (van Dijk, 2006)6. A lack of necessary technical knowledge may prevent people from using the internet in a socially or economically meaningful way.

In review of the empirical evidence, one study explores the the Digital Divide by analysing the concrete developmental impacts of internet access on small businesses in Tanzania and South Africa. It found that the internet is mainly used for basic communication instead of producing or disseminated the type of information than can support innovation and industry. In summary, despite the penetration of mobile technology throughout the continent, “African industries are by-and-large thinly integrated into the global informational economy and ICT diffusion is doing little to reduce the economic inequalities that have marked the region’s relationship with the West, and now East, for decades.” (Murphy and Carmody, 2015)7 The transformative potential of the internet is consequently wasted.

Another study explores the consequences of unequal technological diffusion within a country. By using data from more than 12,000 households in rural India between 2005 and 2012, it determined the impact of the rapid spread of mobile phones – from 3% to 75% of households – on healthcare access for digitally excluded households. The result was that the “the fast pace of mobile phone diffusion makes it harder for poor people without phones to access essential health services. In other words, non-adopters are increasingly excluded from health services if everyone around them starts using mobile phones, leaving them worse off than before” (Haenssgen, 2018)8. New technologies can therefore create divides between poor parts of the population that weren’t previously there.

It is wrong to assume that the number of people with internet access increasing means the Digital Divide is disappearing. The differences are in fact multidimensional. Each new technological innovation - like smarter devices or faster broadband – also engenders a new diffusion process, and so the gaps are constantly moving. There is little doubt that the internet has the potential to improve countless lives around the world, but this potential is too often wasted. In order to fully realise the transformative power of the internet, it is imperative that we acknowledge and understand the nature and nuances of the Digital Divide.